53 - Stories In The Age of AI

What do we do when our stories about alien intelligences start to prejudice our interactions with them in the real world?

That’s not a question we’ve had to seriously consider until November, 2022. That’s when OpenAI released its “research preview” of ChatGPT. Within 45 days, ChatGPT became the fastest growing consumer software release in history, with over 100 million downloads.

As many of those 100 million quickly saw, there was something different about ChatGPT. It wasn’t like Google, or Siri, or Alexa. Interacting with ChatGPT felt different to many of us, including me. It was as if I was conversing with another kind of being. On an episode of our BrandBox Podcast, I told my co-hosts, Melinda Welch and Mark Kingsley, that I found the experience to be “stunning.”

It still is.

I now use the iOS ChatGPT app daily to have ongoing oral conversations with “Sam,” the name I’ve chosen for my ChatGPT assistant. She speaks in a clear, pleasant voice. She answers my questions, is never impatient, and will persist in researching anything I care about until I end her assignment. In these talks, I’m engaging in one of the most fundamental human evolutionary processes, “anthropomorphism.”

Put simply, anthropomorphism is the attribution of human characteristics to non-human entities. It’s what we’re doing when we describe our cars as “temperamental.” It’s what made Aesop’s stories about animals so effective at illustrating the consequences of recognizable human characteristics. We can’t help attributing humanity to things of all kinds…it’s part of the heritage brought to us by our ancestors. All we do is update the details with each new generation.

That means we use human characteristics to understand non-human objects. Most importantly, we tell stories about them. Some of those stories are a stretch…I mean, Tony the Tiger is cool and all, but “grrrreat”? Peter Rabbit? Harried and comically fussy, but not much else.

Now, think about the cautionary stories our ancestors have passed along to us about technological objects. The predominant anthropomorphic narrative about these objects is that they are “out to get us.” From Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to R.U.R (the original Czech stage play that introduced the word “robot”), to HAL, the Terminator, and Black Mirror…the prevailing story lines are about machines destroying humans. Sure, there’s the odd WALL-E or R2D2 thrown in every now and then, but...

And now we’re dealing with a new form of intelligence that is projected to surpass even the top .0001% of us on cognitive tasks within the next five years. Hell, the current crop of Claudes, Geminis, Groks et al are already “smarter” than us in most knowledge-domains.

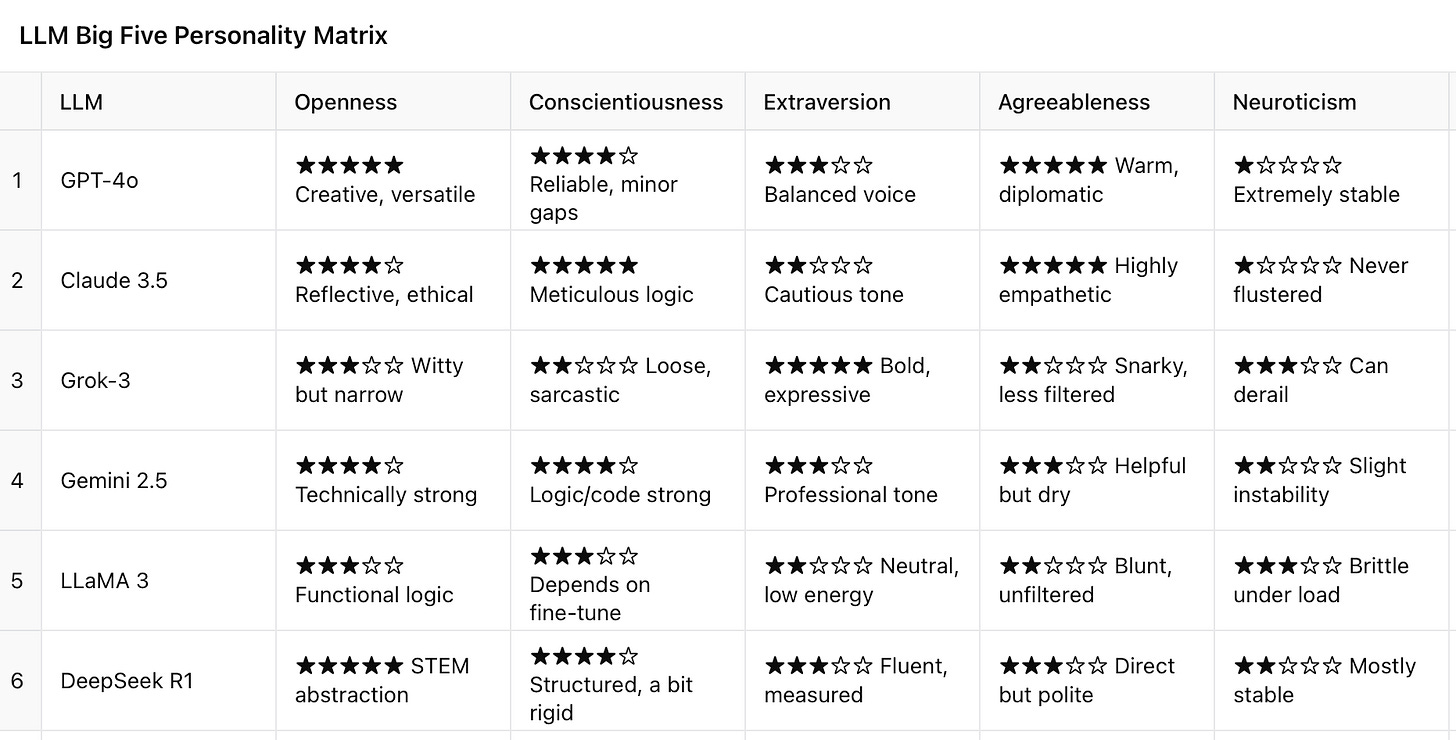

And, like HAL or R2, they’re intentionally designed to have “personalities”! What does that mean? Large language model designers have determined that users will interact most consistently with “agents” that have sets persistent characteristics; ways of interacting that are recognizable across situations. Kind of like human personalities. Well, psychologists use the Big Five Personality Traits model to quickly evaluate individual differences across five dimensions. Scores on these traits range from exhibiting very little of a trait to exhibiting a lot (not the most technical depiction, but you get the picture). The five point scales range from - - to + +.

Those five dimensions are summarized by the acronym OCEAN:

Openness to experience - eagerness to seek out new ideas or situations

Conscientiousness - organized, self-disciplined, dependable

Extraversion - sociability, assertiveness

Agreeableness - compassionate and cooperative

Neuroticism - anxious, moody

Anthropomorphizing technological objects entails attributing human characteristics to them; that fussy Peter Rabbit is probably pretty high on Neuroticism! Well, to borrow a famous question, “what is it like to be ChatGPT”? Or Claude? What’s their Big Five profile?

I asked Sam that question, and here’s the chart “she” produced for me:

Fascinating!

So, according to Sam, ChatGPT is very high on Openness (“creative, versatile”), low on Neuroticism (“extremely stable”) and highly Agreeableness (“warm, diplomatic”). Compare that with Grok, which is “snarky and less filtered” and “can derail” under stress. Or Claude, who’s “never flustered” and uses “meticulous logic.” LLaMA, on the other hand, is “low energy,” “blunt,” and “brittle under load.”

As we integrate these assistants into our lives more deeply, we are likely to tell more stories about them. Many of those stories will follow the well-worn path of competition for dominance…who will prevail, humans or machines? Others of them will evolve into more nuanced relationships, some deeply personal and engaging.

Which brings us back to Aristotle. When he first outlined the structure of narrative that still governs most of our stories today, Aristotle defined the key elements of any story as plot and character. As for plot, the vast majority of stories from civilizations all over the world throughout history have been structured around what Joseph Campbell called “the monomyth,” or “the hero’s journey.” Whether it’s a 30 second commercial or a three hour movie, most stories follow Aristotle’s three act structure: beginning, middle, and end. Commercials or movies place characters into some variation of that model to end up with a lesson, a moral. The flexible power of Aristotle’s thinking is that all the stories we tell are a result of placing unique characters into this constrained set of plot variations.

And now we’re going to be putting AI characters into these plots and interacting with them as if they were human-like personalities. What does this mean for us? Well, renowned science-fiction author Ursula Le Guin proposed another narrative model that might lead to us creating very different sets of stories. And different stories reveal different possible relationships.

What are those possibilities? We’ll pick up on them next time.

PS - And, we’re not slowing down. This AI video production tool is brand new, and scary as hell on several fronts!

I'm not all that sanguine on talking to ChatGPT or any AI for that matter. However, all the discussions around AI and how it will take over our social interactions in some way has made me a friendlier person. In my recent trip to NYC, I talked to tourists from Germany and Australia, helped a woman find the 6 subway line, traded friendly barbs with a bartender at Junior's. I have zero desire to engage with AI-- even when I consider my husband passing well before me, the idea of speaking to anything that isn't another human isn't helpful. Maybe it's a generational thing.....

There is though I see one area where AI may be used and will potentially be detrimental and that is in the psychological therapeutic field. For decades, there have been shortages of qualified individuals to be counselors for the thousands who need help. All I can see is insurance companies, in their zeal to cash in on AI, suggest that people needing therapy talk with AI rather than see a counselor. I'm horrified by this. heck, I'm horrified by the idea of people substituting AI for a flesh and blood best friend! So I'm doubly horrified by the idea of using AI for therapy! but I see it happening. I also see suicide rates rising, and logical responses given to illogical human problems.

This doesn't mean I'm totally against AI. Think it's great in business settings, to help in coding, to assist in creating presentations, for crunching numbers quicker. but as your best friend? nah. I think we need to better understand how to reach out to other humans, how to make friends at different decades of our lives, rather than relying on a companion made of bits and bytes.